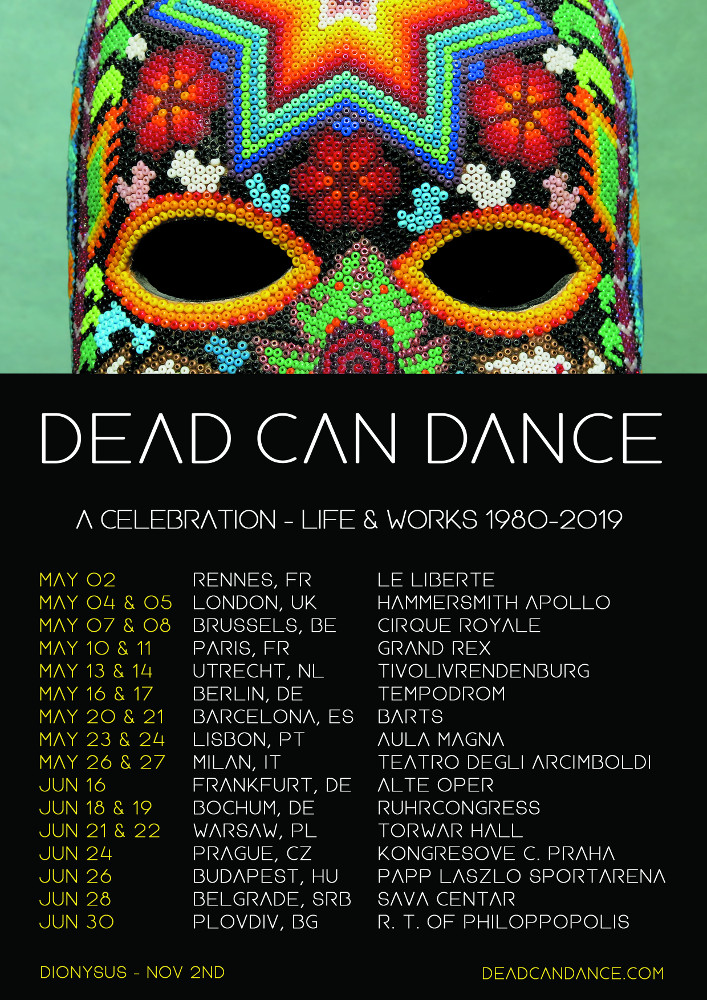

Since their inception in Melbourne in 1981, Dead Can Dance have been informed by folk traditions from all over Europe, not just solely in terms of instrumentation, but also by secular, religious and spiritual practices.

The story to their forthcoming album Dionysus took shape as Brendan Perry became fascinated by long-established spring and harvest festivals that had their origins in Dionysian religious practices throughout Europe. The presence of the religion was suppressed during the ideological control of Christianity and Islam since the Roman Empire, and so the influence that Dionysus still had on these festivals would continue to manifest itself albeit in a more censored form.

Dead Can Dance’s latest album brings to the fore the rites and rituals that today continue to be informed by the Greek god, with the album’s seven movements representing different facets of the Dionysus myth and his cult.

The musical form of Dionysus is that of an oratorio, which has informed spiritual and secular pieces of music as far back as the early 16th century.

ACT I – Sea Borne announces Dionysus’ arrival from the east by ship. This movement is crucial to understanding Dionysus as an outsider god – ‘the god that comes’ – central to Ancient Greek city religions that affiliate him with the protection of those who do not belong to conventional society, and anything which escapes human reason.

ACT I – Liberator of Minds, with Dionysus being known as ‘he who lends men’s minds wings’, the album’s second movement conveys the use of hallucinogens and mind-expanding drugs that are associated with him as well as breaking free from the constraints of social norms within society.

ACT I – Dance of the Bacchantes, invokes the rite that Dionysus’ female followers took part in, abandoning their domestic duties for trance-like processions and dances.

ACT II – The Mountain, the first movement of the album’s second Act, the listener will find themselves visiting Mount Nysa. This mountain was Dionysus’ place of birth, where he was raised by the centaur Chiron, from whom he learned chants and dances together with Bacchic rites and initiations.

ACT II – The Invocation represents the chorus who summon the god to participate in the harvest ceremony which also refers to his pre-eminence in the creation and birth of Greek theatre and tragedy.

ACT II – The Forest, the call to abandon worldly and material pursuits and return to a primeval enlightened state of being as in the Hindu tradition of Vanaprastha “departure to the forest” which is seen as the final stage in human spiritual development.

ACT II – Psychopomp, the final movement sees Dionysus in his role as a guide to the afterlife, where he escorted dead souls to Hades.

With the sway that Dionysus’ story still has on contemporary paganism in Europe, the voices on this album see Perry imagine a small community or village with people in communion with each other during a time of celebration or ritual. Singing at times via chanting and call and response, the language that these people sing in is fictional, not representing one country or group in particular. Instead, the solo and chorus voices become a means to convey emotion beyond the boundaries of language itself. As with many previous Dead Can Dance albums, there is no libretto for the voices.

Perry’s radical revisal of his artistic space led him to take inspiration from the natural environment around him, especially animal calls and natural sounds which Perry mimics on this new album using an array of folk instruments from across the world. Across the two years in which he made Dionysus, Perry gathered together a world-spanning array of percussion including the Daf (Iranian frame drum) and the Fujara (Slovakian shepherds flute). As with the rest of the Dead Can Dance catalog, rhythms inspired by world traditions play a key role, with tracks seeming less like songs and more like fragments of a cohesive whole. Perry blends all of the album’s elements together using field recordings and chanting, including a goatherd in Switzerland, beehive’s from New Zealand, and bird calls from Mexico and Brazil. Perry uses this not only to invoke the album’s atmosphere and symbolic references but also to demonstrate how music can be found everywhere. On Dionysus, sounds blend into one another to create an esoteric, atmospheric, at times magical realist experience for the listener.

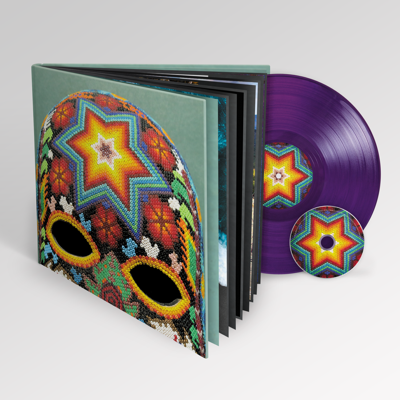

The album’s story may be prominently inspired by that of Dionysus, but its cover detail came from a mask made by the Huichol of the Sierra Madre Mountains in Mexico – famous for their yarn paintings and objects meticulously decorated with beadwork – who use peyote as a sacred rite and ritual for the purposes of healing and mind expansion. At its core, it’s this which is key to understanding the sentiment of Dead Can Dance’s latest opus – a celebration not just of humanity but of humanity’s working alongside nature with respect and appreciation.